Written and published by Thi Hoang of the Global Initiative Against Transnational Organized Crime.

American historian Melvin Kranzberg once said, ‘Technology is neither good nor bad; nor is it neutral.’ The reality is that technical innovations often have ecological, social, political and economic consequences that may undermine their initial purpose. In the human-trafficking economy, the same corollary applies, and technology can prove to be a double-edged sword.

The Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE) and Tech Against Trafficking, a coalition of global tech companies and experts leveraging technology to help eradicate human trafficking, have jointly launched ‘Leveraging innovation to fight trafficking in human beings: A comprehensive analysis of technology tools’.

The report finds that while technology can be an effective tool in the drive to prevent human trafficking, it has simultaneously enabled traffickers to achieve greater efficiencies.

Specifically, technology tools are used by anti-trafficking stakeholders to prevent trafficking circumstances by enhancing technological capabilities among vulnerable and marginalized groups and communities (e.g. children and ethnic minorities); to investigate and prosecute criminal activities; to protect and support survivors; and to equip stakeholders with technical capacities and innovative approaches.

The flipside of the digital coin is that traffickers also deploy technology tools to scale up their market reach, deliver new types of illicit services, such as livestreaming of sexual abuse and exploitation, to innovate their operations, to target more victims and to launder criminal proceeds anonymously.

This dual aspect of the law of technology is the central focus of the new publication, the first to analyze on a global scale how anti-trafficking stakeholders – and traffickers – deploy technology.

The report features a global landscape analysis of technology tools that have been developed to counter human trafficking. Landscape mapping of anti-trafficking tech tools is a core project of Tech Against Trafficking’s research, a multi-stakeholder initiative that uses datasets from the private sector (including Amazon, AT&T, BT, Microsoft and Salesforce.org), and intergovernmental and civil-society organizations. Tech Against Trafficking and the GI-TOC conducted global outreach in order to include regional and local technology tools, making the mapping more comprehensive. The result was greater inclusion of non-English technology tools developed and operating in the Global South, especially with the support of international NGOs and several UN agencies.

The following are some of the key takeaways from the landscape analysis, which includes more than 300 technology tools.

- Technological innovations must ensure engagement and participation of the target user groups they are intended for. Often, technological solutions are developed without proper consideration for the target users’ own needs and digital capabilities, or for technological infrastructure and the local environment. These innovations risk being a solution that creates a problem.

- Research before innovation. There are duplications of efforts evident in the landscape mapping. Tools with similar functions, goals and target users have been developed in different parts of the world. It is strongly recommended that stakeholders collaborate and replicate existing solutions, rather than reinventing the wheel. Technology developers are also highly encouraged to make solutions not only publicly available, but also open source, in order to enhance collaborations in the field (given that more than three-quarters are proprietary technologies).

- Without due follow-up, tools are rendered obsolete and might even detract from their initial purpose, potentially depriving vulnerable groups of a valuable resource.

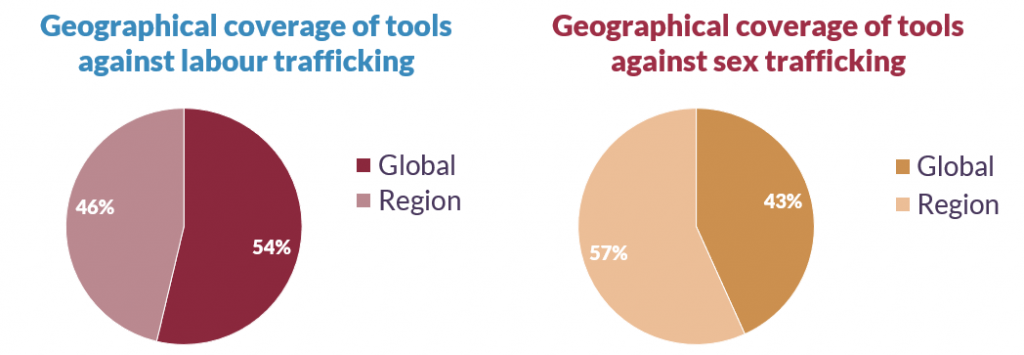

- It was found that tools developed to combat labour trafficking tend to have a global scope, whereas anti-sex-trafficking tools focus more on a regional level. This can be explained by the globalized nature of today’s supply chains (and hence the global scope of anti-labour-trafficking tools), in contrast to the regional and national differences in perceptions and legislation surrounding sexual exploitation and forced marriage in different parts of the world (which explains the more regional focus of anti-sex-trafficking tools).

The landscape analysis also looks at different stakeholder groups (the private sector, NGOs, law enforcement, etc) and the respective ways in which such entities deploy anti-trafficking tools (such as victim/trafficker identification, data trends and mapping, awareness raising etc). In so doing, the study was able to identify trends and gaps in the tools’ utility. For example, businesses are encouraged to capitalize on tools designed to give voice to and empower workers in their supply chains, and to put in place corporate safeguard mechanisms that utilize victim case management and support innovations.

With this publication, the OSCE and Tech Against Trafficking aim to equip stakeholders in the field with a comprehensive picture of the increasingly important role that technology plays in global human trafficking developments, so as to avoid duplication of efforts and to join forces in countering and addressing the root causes of this criminal industry.